He left the company in late 2014, as the nefarious projects mounted and the toxicity, he says, became too much to bear. “Nix was a monster,” Wylie writes. “Bannon was also a monster. And soon enough, were I to stay, I worried that I would become a monster, too.”

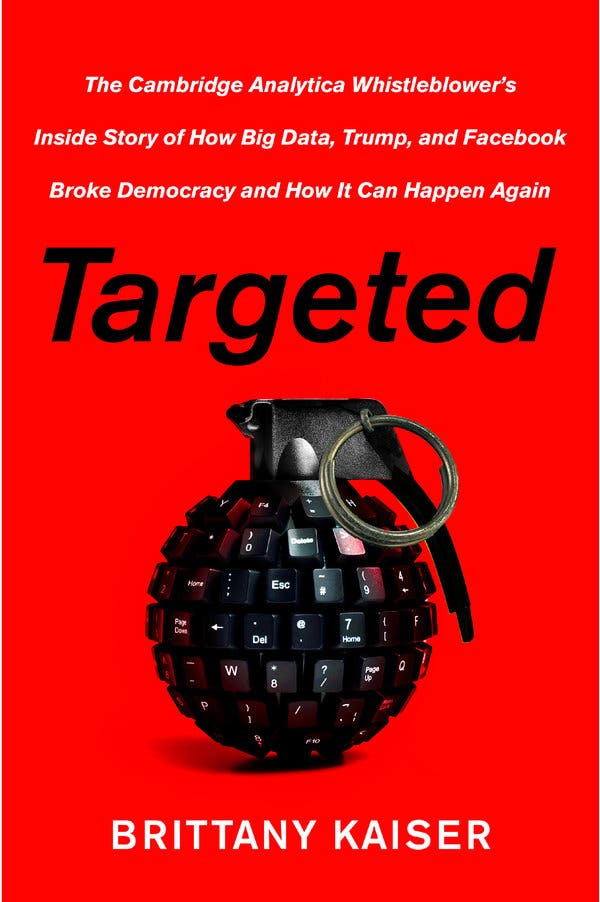

A month later, Nix hired Brittany Kaiser to work in “business development.” Like Wylie, Kaiser says she was a liberal — though unlike Wylie, she so strenuously insists how fundamentally decent she is that her awkward remonstrations have a perverse effect on her credibility. She is frequently “humbled.” She is forever a “human rights activist.” She is worldly and smart and spectacularly connected while nevertheless “vulnerable” and helplessly “naïve.” All of this makes for a bizarre book: “Targeted” has the slightly sweaty smell of someone trying to launder her reputation.

Kaiser knows she has a lot of explaining to do. She stayed with the company for more than three years, coming out as a whistle-blower only after a tough exposé by Carole Cadwalladr in the Guardian delineated Cambridge Analytica’s attempts to sway a Nigerian election and highlighted Kaiser’s role in the plan. (Kaiser takes frequent swipes at Cadwalladr in “Targeted,” asserting, without offering much by way of evidence, that the journalist was “dead set on defaming me.”)

The recent documentary “The Great Hack” includes footage of Kaiser speaking on a pro-Brexit group’s panel at a public event; another scene has her worrying about a visit she paid to Julian Assange a few months after the 2016 election. In “Targeted,” she acknowledges helping develop a relationship with the oil company Lukoil, which is famously linked to the Kremlin, but says she had no idea it was a Russian company.

When it comes to personal revelations, the book is opaque and exceedingly repetitive, as if the prose had been pushed through the messaging mill of a P.R. firm. Kaiser concedes she did everything for the money — but even as she admits her actions might look “selfish,” she maintains she was ultimately selfless: Her salary, she says, was used to help her parents, who had been wealthy enough to send Kaiser to Phillips Academy, in Andover, Mass., but had lost everything since and were living in dire financial straits.

In their respective memoirs, Wylie and Kaiser cast aspersions on each other, which seems especially curious for two people who apparently have never met in person. Wylie even challenges the notion that Kaiser is a whistle-blower, depicting it as a conveniently timed rebranding; Kaiser calls Wylie a “disgruntled employee,” and seems incredulous that this “pink-haired high school dropout” was getting so much positive media attention. (That she calls herself “the Cambridge Analytica whistle-blower” in her subtitle is extremely telling, though not in the way she intends.)

Still, the documents Kaiser provided to authorities corroborated Wylie’s revelations, and regardless of her reasons for coming clean after breaking bad, she eventually talked to journalists on the record, when most other employees kept quiet. Whistle-blowers are often complicated people with a tangle of motives, and dueling memoirs aren’t necessarily the ideal place to tease out the definitive truth. As Kaiser put it to herself after she realized that refusing to ask meant she couldn’t tell: “It’s above my pay grade.”

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates