If she’s going for the uncanny, then some of her many, brief plots are too flimsy, not grounded enough in the recognizable, to succeed. A seamstress suddenly “decides to give up people,” making clothes instead for mannequins, a car, a teakettle. There’s no more to the story, and it’s too bad: Given more space, it could’ve been almost charming.

Polek’s imagery, though, comes through like flashes in a silent film. In one memorably vivid scene, a landlord shows a couple a video of herself as a child, smashing strawberries into sheep’s wool. Another narrator’s grandfather falls in love at 26 with a woman who loves flowers; one day he sneaks into her house to water all her plants. But he doesn’t stop there, watering her quilt, her phone and her carpet. This may seem destructive, or cruel, but in Polek’s world, it feels more like beauty.

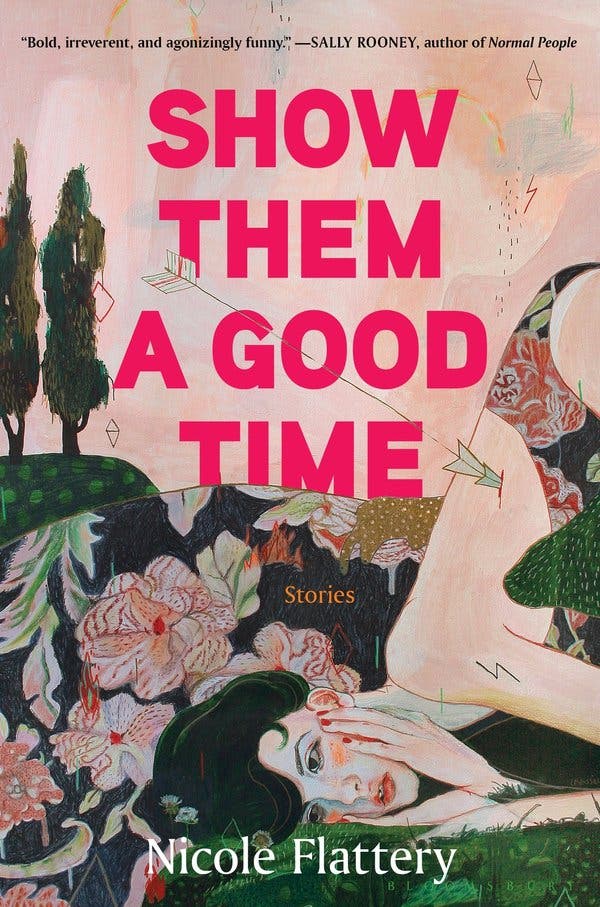

SHOW THEM A GOOD TIME

By Nicole Flattery

238 pp. Bloomsbury. $24.

Like Cohen’s collection, Flattery’s “Show Them a Good Time” is populated with unlikable women, or at least ones with gaping, gnawing flaws, ones who live and observe their lives in off-kilter ways.

Flattery’s writing is like a fever dream; the details are lucid, but the basics (place, time) are disorientingly hazy. Perhaps this rootlessness is intentional; what she seems to care most about is talk — what it can and can’t do, how it can hurt, how it can be the source of regret. In “Hump,” a woman recalls her dead father’s final regret: that he didn’t talk more. “He surmised, through a mouthful of diabetic chocolate, that he had only spoke 30 percent of his life. It was a dismal percentage.”

Many of Flattery’s protagonists have endured some sort of trauma, but the events are so buried we feel we’re getting only their bitter remains, and we’re unsure if those remains are strength, or apathy. In the title story, a woman remembers her abuse as a cliché: “Usually when he was halfway through hitting me it would occur to him just how obvious he was.”

As though in flat rejection of the victim narrative, Flattery’s women can be spectacularly mean. In “Track,” a woman with a famous comedian boyfriend starts to leave nasty comments on his fan page, using his dead mother’s name as a pseudonym. Like other characters in this collection, she’s desperate to communicate directly; she just doesn’t know how. So she prints out the meanest post and puts it in her boyfriend’s coat pocket.

The cruelty in the worlds Flattery draws makes the tender moments in her stories all the more affecting. In “You’re Going to Forget Me Before I Forget You,” two sisters have a series of phone conversations, about the narrator’s children’s-book writing, about her sister’s pregnancy. They almost always speak at night, the narrator back in her hotel room, on book tour. There’s a gloominess to this story that comes from lingering childhood trauma, but also a neediness, and a romance: At one point the pregnant sister begs her to blow cigarette smoke to her through the phone. In between these dialogues, the narrator thinks about the past, glances back at the pains of the sisters’ young lives, even calls an ex. “Would you forget me if you could?” she asks him. “No,” he says. “I wouldn’t.”

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates