There are scores of novels about World War II, but far fewer about what happened next. When we meet Zofia Lederman in August 1945 in Monica Hesse’s THEY WENT LEFT (Little, Brown, 364 pp., $17.99; ages 14 and up), she has spent her adolescence surviving the Birkenau and Gross-Rosen concentration camps. But as her liberators celebrate the end of a nightmarish era, Zofia can’t seem to join in.

“What did they mean, it was over?” she asks. “What was over? I was miles from home, and I didn’t own so much as my own shoes. How was any of this over?”

Zofia is driven by a mission: to find her younger brother, Abek, the only other member of her family not sent left, to the gas chambers, by the camp guards. When he doesn’t turn up at their apartment, Zofia leaves Poland to search for him.

At Foehrenwald, a displaced persons camp in Germany, she finds the possibility of a new life — and of romance, with an enigmatic man consumed by a secret. But a black hole in her memory protects some trauma she doesn’t want to touch, its dreadful shadow looming ever larger as the book goes on.

Hesse writes with tenderness and insight about the stories we tell ourselves in order to survive and the ways we cobble together family with whatever we have. When the plot twists come, they are gut punches — some devastating, others offering hope.

The number of living people who witnessed the horrors of the Holocaust firsthand is rapidly shrinking: Fewer than 200 survivors attended this year’s 75th anniversary memorial of the liberation of Auschwitz, many of them unlikely to see the 80th. This dwindling number makes stories like Zofia’s all the more crucial.

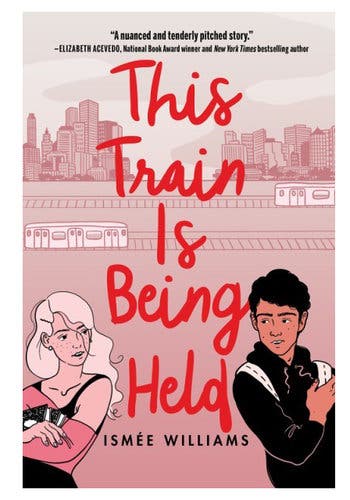

On the New York City subway, you are more likely to get kicked in the face by a “showtime” dancer or have your pizza carried off by a rat than to find true love. But the protagonists of Ismée Williams’s charming urban romance THIS TRAIN IS BEING HELD (Amulet, 289 pp., $17.99; ages 13 and up) defy those odds.

Alex Rosario is a baseball star from a working-class Dominican family. Isa Warren attends private school, lives in a doorman building and does ballet. The 1 train is their Verona, its screeching brakes their violins. But all is not sneaky smooches, hidden love notes and dancing bachata between the subway poles. While Alex rides back and forth between his overworked mom and his domineering dad (who believes baseball is his son’s only ticket out of poverty), Isa is so busy taking care of her volatile Cuban mom (who doesn’t want her daughter to date Latino boys), her recently unemployed dad and her mentally ill older brother that she has no time left for herself, hiding her struggles behind a perfect bun and a shiny smile.

We root for these young lovers — the self-conscious poet with the killer fastball and the shy ballerina who would take a bullet for those she loves — as they learn to let their guards down and be more honest with each other, and with themselves. When their story rolls into its final stop we’re sad the ride is over but delighted we caught this train.

As a queer black boy growing up in Plainfield, N.J., George M. Johnson longed for books about kids like him. But such stories, especially true ones, were few and far between. So he took that Toni Morrison line about creating the nonexistent books you want to read to heart: He sat down and wrote a book for his younger self.

“I realized that I wasn’t just telling my story,” he writes in the introduction. “I was telling the story of millions of queer people who never got a chance to tell theirs.”

The result, ALL BOYS AREN’T BLUE: A Memoir-Manifesto (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 320 pp., $17.99; ages 14 and up), is an exuberant, unapologetic memoir infused with a deep but cleareyed love for its subjects. Johnson lays bare the darkest moments in his life with wit and unflinching vulnerability, from the bullying he suffered as a child to the losses of his cousin — an early model for him of what a joyful queer life could look like — his fraternity brother and his grandmother, who died as Johnson was working on the book and whose presence looms largest in it.

In one particularly moving chapter, Johnson recounts how he was molested by a trusted family member — a story addressed to his now-dead abuser with startling empathy.

Johnson initially intended to end each chapter of his “memoir-manifesto” with “solutions for all the uncomfortable or confusing life circumstances I experienced as a gay black child in America.” Thankfully, he changed his mind. While there are still some bits of sermonizing, mainly in the first half of the book, the most rewarding moments come when Johnson allows himself to sit with uncertainty — not offering neat solutions to life’s messiest problems but simply telling readers: I see you. I feel you. I’ve been there, too.

In Meredith Tate’s THE LAST CONFESSION OF AUTUMN CASTERLY (Putnam, 346 pp., $17.99; ages 14 and up), Autumn Casterly is a high school senior who spends her spare time dealing pills, gathering blackmail material on her classmates, beating up snitches and engaging in petty larceny. Ivy Casterly is a sophomore who spends her spare time with the Nerd Herd, a “Star Wars”-loving, board-game-playing gang of Friendly’s sundae enthusiasts. There’s no doubt in anyone’s mind which sister is the good kid and which one is the lost cause.

Anyone’s except Ivy’s, that is.

When Autumn goes missing, the adults all write it off as just another incident in a long string of delinquent behavior. But Ivy is convinced that something is wrong. No matter how callous her sister may be, she is still her sister. And if she’s in trouble, it’s Ivy’s job to help.

Ivy’s instincts are spot on: Autumn has been brutally beaten and abducted in an apparent drug deal gone wrong. Suspended between life and death, Autumn leaves her body and follows the little sister she pushed away.

Tate toggles effectively between the sisters’ points of view: Ivy’s dogged attempts to untangle the life of a girl who armored herself with secrets and Autumn’s desperate haunting of the world she may shortly vacate for good.

One by one, the puzzle pieces start to click into place as this breakneck thriller accelerates, turning up skeletons that the sisters, their family and their community thought had been shoved permanently in the closet.

Autumn’s disappearance, Tate writes in the author’s note, is a metaphor for the way victims are so often gaslighted and shamed. Autumn spends much of the book invisible and “shouting into the void.” But this tale of undeterred sisterly love is a primal scream that will not be ignored.

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates