Peter Wollen, who in a wide-ranging career wrote the influential film theory book “Signs and Meaning in the Cinema,” directed or co-directed films, wrote screenplays for others and curated art exhibitions in New York and elsewhere, died on Dec. 17 in West Sussex, England. He was 81.

His wife, the writer and artist Leslie Dick, said the cause was Alzheimer’s disease. He had been in institutional care in England for 14 years, she said. Born in England, he had taught in the United States for many years.

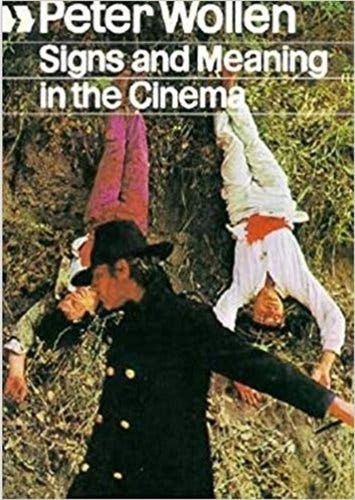

“Signs and Meaning in Cinema,” published in 1969, resulted from work Mr. Wollen was doing for the British Film Institute on a book series called “Cinema One.”

“I was editing the series,” he said in a 2001 interview with Serge Guilbaut and Scott Watson of the University of British Columbia, “and I commissioned myself to write a book.”

The volume is widely credited with helping to re-energize film studies. The book had three sections: on the Soviet director and theorist Sergei Eisenstein and his influence; on auteur theory; and on “The Semiology of the Cinema,” or the language of film. The book was published at the end of an eventful decade in England and the United States, both in politics and in the arts, and Mr. Wollen argued that cinema studies needed to be less cloistered.

“For much too long film aesthetics and film criticism, in the Anglo-Saxon countries at least, have been privileged zones,” he wrote in the introduction, “private reserves in which thought has developed along its own lines, haphazardly, irrespective of what goes on in the larger realm of ideas.”

“Signs and Meaning in the Cinema” was reissued a number of times, with additional essays by Mr. Wollen, including some he had written under the pseudonym Lee Russell for New Left Review in the mid-1960s. It was widely discussed in academia, and Mr. Wollen would soon be part of the academy as well. He taught at Brown University, New York University and other institutions, including, from 1988 until his illness set in, the University of California, Los Angeles.

Mr. Wollen didn’t just talk and write about cinema; in the 1970s and ’80s he was actively involved in making it. Perhaps his best-known film, which he both wrote and directed, was “Friendship’s Death” (1987), an unusual science-fiction film about an extraterrestrial robot who is on a peace mission but takes a wrong turn and winds up in Amman, Jordan, in 1970, a time of conflict there.

Tilda Swinton, in one of her first film roles, played the robot. In a tribute to Mr. Wollen published by the film website IndieWire, she said “Signs and Meaning” was “the first seminal book I read about film that actually made sense while bopping you to bits with its braininess and taking the engine of cinema completely apart in front of you while making you even more excited to jump in and go racing about in it just as soon as you possibly could.”

Peter Wollen was born on June 29, 1938, in Woodford, northeast of London. His father, Douglas, was a Methodist minister, and his mother, Winifred (Waterman) Wollen, was a homemaker who became a teacher. Mr. Wollen was educated largely at the Kingswood School, a boarding school in Bath, an effort by his parents to give him some educational stability — his father was moved to a new assignment every few years.

His parents were socialists and pacifists, and Mr. Wollen was thinking heady thoughts early.

“I founded a little group at school called the Dada Existentialist Wedge,” he said in the 2001 interview, “and we had pathetic Dadaist Existentialist meetings and events.”

“It was written on my school report that ‘he is in danger of becoming an intellectual,’” Mr. Wollen added. “So naturally when I read that I thought, ‘O.K., that’s what I’m going to be.’”

He earned a bachelor’s degree in English literature at Oxford in 1959. His interest in film coalesced at the university, fueled by a group of friends who were following French New Wave cinema.

After graduating he lived in Paris for a time, absorbing more cinema, and traveled to Tehran before returning to England. There he began writing for New Left Review, which was run by people he had known at Oxford.

At first he wrote only about contemporary politics, but, seeking to expand the scope of the journal, the editors asked him to write film pieces as well. (Explaining why he used a pseudonym, he said, “You can’t write about a lot of different topics under the same name because, if you do, people won’t take you seriously.”)

Paddy Whannel of the British Film Institute was impressed by his film writing and asked him if he would join the institute’s education department.

“One of the basic goals of the education department,” Mr. Wollen said, “was to support anyone who wanted to teach film in schools or universities. And one way to support them was by publishing books which they could use in class.”

That led to the Cinema One series and his own book.

Mr. Wollen took a stab at screenwriting in 1975 as one of several writers of “The Passenger,” a political thriller directed by Michelangelo Antonioni; it starred Jack Nicholson as a journalist who switches identities with a dead man. Michael Wilmington of The Chicago Tribune wrote about it when it had a 30th-anniversary showing in Chicago.

“It’s a movie from the past that still points ahead to the future,” he said, “a cinematic rite of passage that raptly recalls a time when the world may have been as uncertain as now, but the movies were often lovelier and more daring.”

Mr. Wollen married the film theorist Laura Mulvey in 1968 (they divorced in 1993), and together they made a series of experimental films in the 1970s and early ’80s. They also made “Frida Kahlo and Tina Modotti,” a 1983 documentary pegged to an art exhibition they organized for the Whitechapel Gallery in London pairing Kahlo paintings and Modotti photographs. Grace Glueck, reviewing that exhibition in The New York Times when it came to the Grey Art Gallery and Study Center at New York University, found it moderately intriguing but mismatched.

“Though the catalog succeeds in making a case for them — in hindsight — as feminist compatriots,” she wrote, “aesthetically their talents are of such a different order that they simply don’t play together. Kahlo is the reason for seeing this show, Modotti an interesting bonus.”

Mr. Wollen, who curated a number of other exhibitions as well, collected his essays on art in a 2004 book, “Paris Manhattan: Writings on Art.” Two years earlier, he had collected some of his film essays in “Paris Hollywood: Writings on Film.”

In addition to his wife, whom he married in 1993, Mr. Wollen is survived by a son from his first marriage, Chad; a daughter from his second marriage, Audrey Wollen; and a granddaughter.

The opening essay in “Paris Hollywood” is “An Alphabet of Cinema,” a tour through filmmaking one letter at a time. C is for cinephilia, an obsessive fascination with film.

“I remember reading an article by Susan Sontag in which she argued that cinephilia was dead, even in Paris,” Mr. Wollen wrote. “I hope not.”

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates