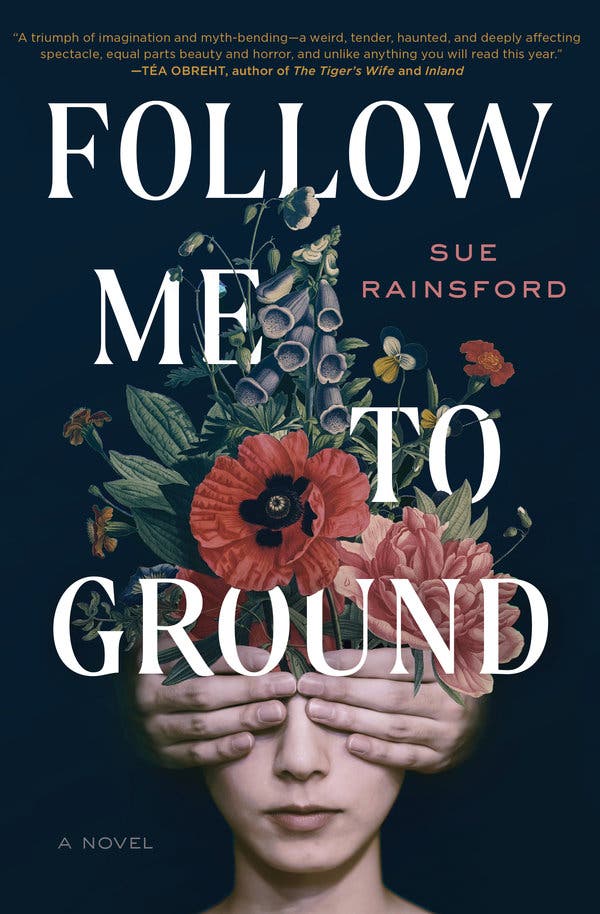

FOLLOW ME TO GROUND

By Sue Rainsford

Sue Rainsford’s “Follow Me to Ground” is the story of an obsessive teenage crush. Except Ada, the young woman at its center, is not technically a teenager; she’s actually been alive for generations, a witch doctor who never seems to grow older. And the bulk of the plot has nothing to do with the boy on whom she has a crush. Told mainly from Ada’s point of view — her tone repetitive, restrained, diffidently fantastical — the novel traces a life warped, then destroyed, by desire.

Ada and her father are both magical, semi-human healers who live in an unspecified town in an unspecified time (trucks, yes; cellphones, no). Ailing townspeople visit their house to have their bodies opened and soothed. The trickiest cases get buried in The Ground, a patch of earth where patients — called Cures — rest in suspended animation until Ada’s father sees fit to resurrect them. Into Ada’s limited world comes Samson, a town boy with a mouth sore and an unusual level of interest in her. Her father disapproves, but no matter; Ada is full of new lust. But Samson has some issues, and so Ada attempts on him the one form of human interaction she’s mastered: healing.

Refreshingly, the novel disregards the predilections of contemporary literary fiction and instead veers toward allegory. No one in this book is Forsterishly “round”; characters lack agency; they are created or possessed or curiously always themselves. Even Ada has little sense of her own motivations. Many of her major moves are accidents.

Only her interest in Samson pushes her to go against her father’s wishes. He is concerned that Samson is not all right in the head, and their healing powers don’t extend to mental illness. But she feels she’s “only been alive a little while. Meaning only since I met Samson,” and this feeling — of coming alive — is what she most treasures. As her quest for selfhood continues, Ada becomes an amoral monster of longing, pushing to cure Samson while sociopathically disregarding anyone who would stand in her way.

In so severely limiting her heroine’s humanity, Rainsford has set herself a difficult task, at which she only partially succeeds. Ada is a kind of golem, created by her father out of a tree branch, and her childlike voice tends toward quick, superficial narration. But when the book slips into horror at the end, it becomes legitimately frightening: Alone late in my apartment, I closed the book 50 pages from the end, feeling that it would be more prudent to finish it by the light of day.

What’s best in the novel is its idiosyncratic vision of the meaning of girlhood and first love. Rainsford draws the coercions of men without contemporary political referents, the natural world without the fatalism of typical eco-horror. The book refers to itself only, and it is fertile ground for pairings: between The Ground and a womb; The Ground and a cemetery; Samson and Ada’s father; pregnancy and possession. The tale pulses with images of opening and entering, into the ground, into patients’ bodies, in sexual union. The suggestion is that a teenage crush is an experience of haunting and being haunted, and that maturity comes through a process of utter, ruinous self-absorption.

But if a story is to be this fast-paced, it ought to be more explicit about its intentions; all the subconscious, blink-and-you’ll-miss-them allegories give the feel of a maddening puzzle. Those excellent late horror scenes, and the angst-ridden, semi-creaturely protagonist, deserved more time to develop. In its spareness, its unwillingness to clarify or expand, its ambiguous evocation of the satanic, the book itself seems buried in the ground.

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates