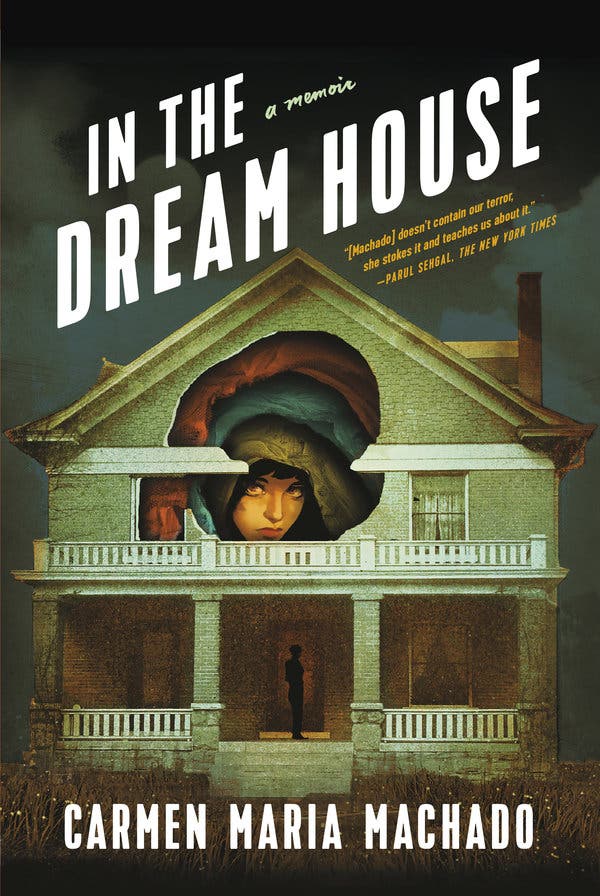

In Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir, “In the Dream House” — her debut story collection, “Her Body and Other Parties,” was a finalist for the 2017 National Book Award — doorknobs recur not as a clumsy or coercive symbol, but as evidence of Machado’s gift for narrative patternmaking. Through repetition, she arranges the full arc of her traumatic relationship with an abusive woman, who volleys between tender manipulation and explosive rage. Machado blueprints a framework for love turned sick bay. She is careful not to collate the terms “house” and “home.” She seldom abandons an image, as if waiting for it to serve its central purpose, which it always eventually does.

[ Read an excerpt from “In the Dream House.” ]

Partway through, in a chapter titled “Dream House as Inner Sanctum,” Machado recalls a childhood fight with her parents during which she locked herself in her bedroom. So her parents did something about it: “All I remember is the cold sensation in my body as the doorknob — a perfect little machine that did its job with unbiased faithfulness — shifted from its home as the screws fell away. … How, when it fell, I realized that it was two pieces, such a small thing keeping my bedroom door closed.”

Later, in a chapter titled “Dream House as Sanctuary,” an adult Machado locks herself in a bathroom while her apoplectic girlfriend is chasing her. “I remember sitting with my back against the wall, pleading with the universe that she wouldn’t have the tools or know-how to take the doorknob out of the door.” The bathroom momentarily becomes her safe space, until the memory resurfaces. Terror is twofold for Machado — it sidelines her, but it also shepherds her. Machado’s wit and compulsive post-mortem approach configure her story into a wildly propulsive memoir, an ambulatory survey of the genre.

In it we find Disney villains, “Star Trek” and fairy tales, all organized only slightly more rigorously than the freewheeling elements of Marguerite Duras’s “Practicalities.” There’s the second-person narration, the repercussive sound of “You.” There’s a sweet gym class memory involving dandelions (evocative of both desire and destruction) and a time-lapse that underscores how inconsequential we are. There’s du Maurier, “I Love Lucy” and plenty of driving — but not like in a road-trip movie, more like in a nightmare where the road is barely lit, the car swerves, strangers stay strangers. A deer makes eye contact. There’s a bildungsroman chapter about a blurred relationship with a pastor. A Florida chapter makes a good argument for how everything bad happens in Florida. There’s a déjà vu ingeniously applied on the page, a cinematic telling of predawn light. A history of queer domestic abuse includes the largely untold story of Debra Reid, the only black woman and the only lesbian in the Framingham Eight, a group of women convicted of killing their abusive partners in the ’90s. Machado recounts how when Reid was finally released on parole, she said, “I just want to get an apartment and turn my own little doorknob and use my own bathroom and eat my own food.” Machado tells us that she can’t forget Debra and her doorknob: “I hope she got what she needed.”

Machado writes about enormity somatically: the gut, the rush of blood, the fluids and the feelings, the commotion in our chests — “the simultaneous leap of excitement yanked back by a leash of panic.” It’s easy for writers to prioritize the mind and forget about the body, with its cracks and chronic thrum; but Machado’s work is an aide-mémoire for corporeality.

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates