The dichotomy he thus sets up — between what he perceives as his true, American self and his Vietnamese face — is never quite resolved. A high school teacher takes him to see a production of Oscar Wilde’s “The Importance of Being Earnest,” a gesture that makes him feel “known and seen, not for being Vietnamese but for my passions and ideas.” He arrives home from this buoying, thunderous experience only to quietly tuck it away when he sees his parents. “What did my family really know about literature or theater?” he thinks. “Ironically, the arts were connecting me to strangers, and yet they widened the already yawning gulf between me and my family.”

He never manages to close the gap. His description of his parents doesn’t leave the realm of teenage caricature — his father is violent, abusive and domineering; his mother quiet and submissive. We assume there is inherited trauma, but we don’t know its contours. There are flashes of tenderness and heartache, but over all his parents are voids that obliterate all light and perception. The result is a coming-of-age that is solipsistic in its understanding of its own pain. Even now that Tran is a 40-something husband and father of two, a Latin teacher and tattoo-shop owner in Portland, Maine, his memories are not told with the wisdom of age, but with the arrested development of adolescence. His parents still seem impossibly foreign, trapped in the amber of how white people must see them.

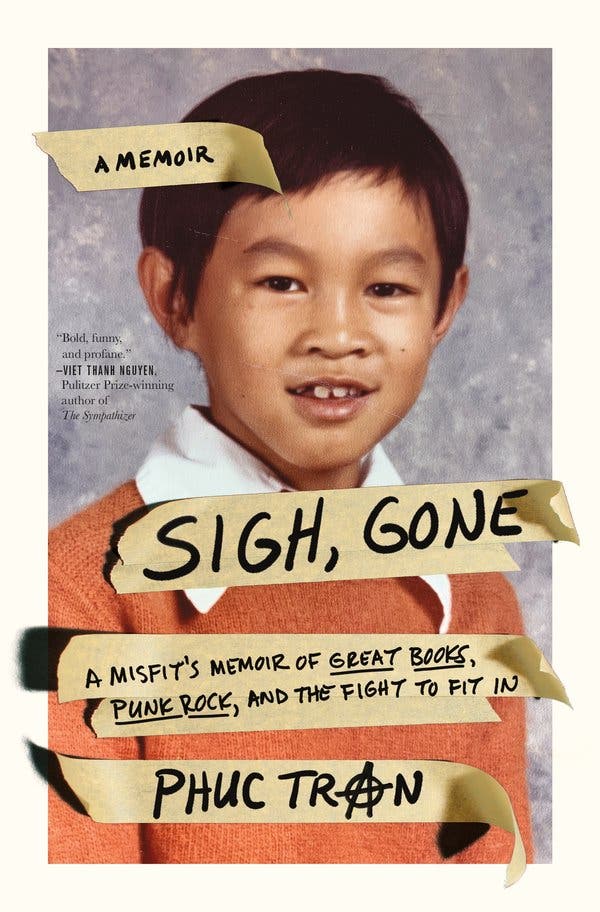

As a result, a mix of resentment and light condescension toward Vietnameseness hangs over the book. Tran phonetically writes out his father’s mispronunciations in English. When his family members speak in Vietnamese, he calls it “Vietnamesing,” as in, “She Vietnamesed feebly.” (Sometimes they “English.”) He introduces the book by describing his hatred for a fresh-off-the-boat Vietnamese transfer student named Hoang Nguyen, whom he sees as “a fun-house mirror’s rippling reflection of me.” But we never meet Hoang again, or know what happens to him. It’s not clear Tran ever inquired. “Sigh, Gone” does not question its central premise that assimilation should be the desired goal for self-making and self-preservation.

Even the white, miscreant members of his skateboarding cohort are drawn with broad strokes; we don’t really know what connects them beyond hooliganism and pack loyalty. Part of what made “Minding the Gap” such an affecting skateboarding documentary was the filmmaker Bing Liu’s ability to connect his own experience of domestic violence with those of his subjects. “Sigh, Gone” lacks this curiosity about the world beyond Tran’s immediate one — whether political or familial or communal — to give the book enough sinew and connective tissue. (Even the way he writes about punk has a superficial flair. Little about the book itself is actually punk, formally or thematically, besides the anarchist “A” on the cover.)

“Sigh, Gone” gestures at interesting ideas without fully engaging in them. Tran recalls an exchange in the supermarket when an old man accosts him and his parents to ask if they are Vietnamese, only to tell them that he fought there in the late ’60s and that it’s a “beautiful country.” It’s an odd exchange, underpinned with menace. Tran recognizes in that moment that his family represents a symbol of patriotic duty for the veteran. The thorny sociopolitical burden he bears — a specifically Vietnamese-American play on W. E. B. Du Bois’s 1897 question, “How does it feel to be a problem?” — is ultimately left unexplored.

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates