Oracle chief technology officer Larry Ellison speaks at a company event in Redwood Shores, Calif., on Aug. 7, 2018.

Oracle livestream screenshot

Among finance types, it’s practically an article of faith that the easiest way to use cash to boost a company’s stock is to buy back shares of its stock — the more the better.

The counterargument: Oracle.

At the software giant, buybacks have spurred a lot of borrowing and spending. Executive chairman and co-founder Larry Ellison’s company has spent roughly $75 billion to buy back stock since its 2016 fiscal year, and $41 billion over the last five quarters, which far outpaces the company’s $19 billion in free cash flow. The multiyear buyback binge cost more than a third of today’s market value for Oracle and has pushed the company into net debt despite sporting $35.7 billion in cash and short-term investments on its balance sheet.

“It’s staggering how much money they’ve spent buying back shares,” said CFRA Research analyst John Freeman, who downgraded the stock to a sell rating on Wednesday. “I’d say 90% of their earnings-per-share growth the last two years has come from buying back shares. He [Ellison] must believe the software-as-a-service companies he would otherwise want to buy are overvalued.”

Oracle spokeswoman Deborah Hellinger declined to comment.

Even though it is still among the 10 U.S. companies with the most cash, according to FactSet Research, its net cash (cash minus short- and long-term debt) is negative $17 billion. That’s about a $32 billion decline since 2016, as the software giant took out a lot of cheap debt to fund buybacks.

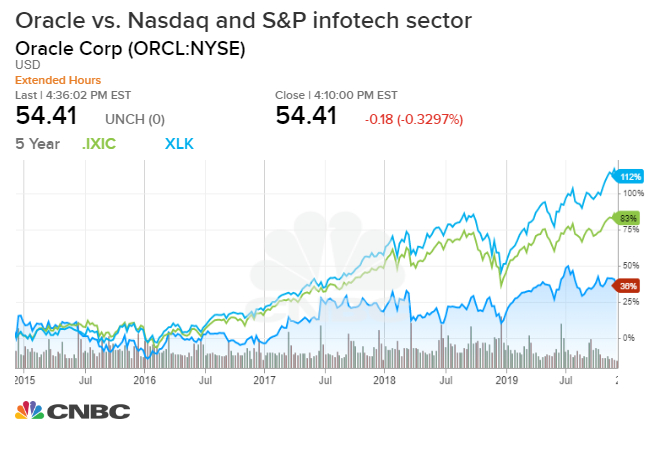

For all that, the stock is up just 35% in the last five years, less than half the gain of the Nasdaq Composite, a common tracker for technology stocks, and a third of the gain of the S&P 500 Information Technology sector.

We’re not sure where this is going. The company has not provided a clear financial policy — has not said, ‘What kind of balance sheet do I want, what kind of company do I want to be.’

Brian Chang

S&P bond analyst

In the short term, Oracle’s finance strategy is causing it problems with bond rating agencies. Standard & Poor’s downgraded Oracle’s debt rating to A+ from AA- in September — the new rating remains investment-grade, but S&P says the debt “is somewhat more susceptible to the adverse effects of changes in circumstances and economic conditions.”

Fitch Ratings cut its Oracle rating to A from A+ last year.

S&P warned of a 1-in-3 chance of another rate cut if Oracle doesn’t slow down its repurchases. At the recent pace of buybacks, its net-debt position could reach twice its annual earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization by the end of fiscal 2020, the agency said.

“We’re not sure where this is going,” said S&P bond analyst Brian Chang. “The company has not provided a clear financial policy — has not said, ‘What kind of balance sheet do I want, what kind of company do I want to be?'”

More on mega-cap company cash strategies:

At Ford, $37 billion in the bank and strapped for cash

Facebook has $52 billion in cash, but big M&A is off the map

$128 billion and growing: Warren Buffett’s cash puzzle

Oracle issued $10 billion in debt in early November 2017, just before the passage of the tax reform act by Congress. Buybacks that were already ongoing before the tax cuts kept surging, drawing down Oracle’s cash from more than $70 billion just after the law passed. Among other provisions that benefited corporations, the law allowed cash held outside the U.S. to be repatriated without paying as much in U.S. taxes, Chang said.

Other tech companies made similar moves timed to the tax cuts, but aside from the much larger Apple, peer companies didn’t buy their own stock as aggressively as Oracle, the S&P bond analyst said.

The big long-term problem is that Oracle has been slow to react to the rise of cloud computing, whose over-the-Internet applications are rapidly taking market share from Oracle’s packaged software that runs on servers controlled by Oracle’s corporate clients. In turn, this means valuations in the software business are migrating rapidly toward software-as-a-service companies like Salesforce and Workday, and toward cloud computing service managers led by Amazon and Microsoft, according to CFRA Research’s Freeman.

Oracle might be in better shape if it had snagged more such companies on their way up, analysts say.

By a series of metrics, Oracle ranks last among a half-dozen cloud vendors ranked in a Nov. 10 Goldman Sachs report, even though it spent $9.3 billion on cloud services provider NetSuite in 2016. Goldman analyst Heather Bellini, who declined an interview request through spokeswoman Megan Riley, has Oracle on the firm’s Conviction Buy list. Morgan Stanley, meanwhile, sees only 1.6% revenue growth in Oracle’s 2020 fiscal year, with all earnings-per-share growth coming from buybacks.

“Whie a no-growth [operating expense] profile and share repurchases keep EPS growth largely intact, the lack of revenue or operating income growth keeps the [stock] range bound,” Morgan Stanley analyst Keith Weiss said after Oracle’s quarterly earnings report in September.

Putting Larry Ellison first?

The aggressive buyback strategy may stem from the fact that Ellison himself owns 35% of Oracle’s shares, according to a proxy statement filed in September with the Securities and Exchange Commission. All companies juggle the interests of bond holders, who would like the company to have more cash and less debt, and shareholders who might want management to reduce the share count as the same amount of profit produces higher per-share earnings, Chang said.

In Oracle’s case, unlike that of similarly-sized tech giants Cisco or Intel, the interests of shareholders virtually boil down to pleasing Ellison, the S&P analyst said.

The company’s delay in embracing the cloud — Ellison was vocally skeptical about it in the early 2000s — let start-ups like Salesforce get a foothold and become too big for Oracle to buy, Freeman said. The company still dominates in client server database software and many enterprise applications, but all of the software industry’s momentum now is behind a different technology paradigm, he said.

The company has its own cloud offerings, and they produced about 21% of Oracle’s sales in the fiscal year that ended in May, Freeman estimated, or slightly more than $8 billion. That’s up from 16% of sales in 2018, which Chang chalked up to “NetSuite doing well.” But it’s well behind Salesforce’s roughly $17 billion in sales for the current fiscal year.

“How does this buyback strategy help you in 2025?” Freeman said. “The cloud guys are eating your lunch. You can’t do $10 billion a year in buybacks and build out your cloud services. There’s no way.”

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates