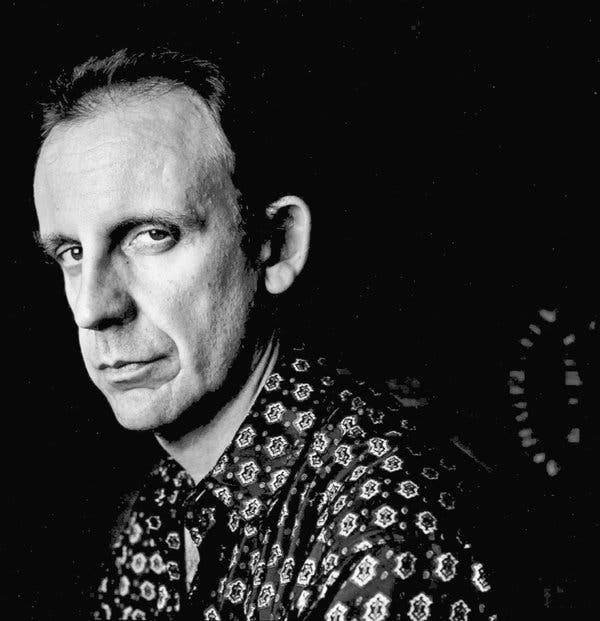

Do you ever feel like the plaything of an enormous fate? Do you sense subterranean forces? Are you interested in estrangement and recrimination? Are you at home with ambiguity? Maybe the novels of Robert Stone (1937-2015) are for you.

A simmering paranoia bubbles under the surface of Stone’s fiction, a paranoia he had a sense of humor about. He once proposed an Alcoholics Anonymous-type group: “The idea was, if you’re feeling paranoid, contact Paranoids Anonymous and they’ll send you another paranoid.”

Reading “Child of Light,” a revealing new biography of Stone by the novelist Madison Smartt Bell, Stone’s distrust begins to make sense. He was not inherently a wild man, but he attracted wildness. It came to him, as if he were coaxing it out of the soil. He fed off the destructive energy.

Stone was born in Brooklyn. His formal education ended with a G.E.D. acquired while he was in the Navy. In the early 1960s, he went west to study writing at Stanford on a Wallace Stegner fellowship. He was already married, and he and his wife had a young daughter. He was a bit of a square.

At Stanford, Stone ran into Ken Kesey, whose vibrating homesteads were the mudrooms and test labs of the Woodstock generation. Stone felt he’d stepped out of black and white and into color. Here was strong pot, free love, spectral amusements, acid trips and epic intellection that no one remembered in the morning. “I felt I went to a party in ’63,” Stone later told an interviewer, “and the party followed me out the door and filled the world.”

About Stone, Kesey would say: “Bob despairs, and there’s something noble about the way he does it. Bob used to get high, stand naked in broken glass and stare at the sky and shout.” Kesey also said that Stone saw “sinister forces behind every Oreo cookie.”

Stone had an intense work ethic. His first novel, “A Hall of Mirrors,” was published in 1967 when he was 30. Set in New Orleans, where Stone and his wife had briefly lived, the novel had a sprawling cast of characters — a pimp-scarred prostitute, an African-American journalist, a “cosmic philosopher” named Farley the Sailor — that included a disillusioned musician who takes a job at a jingoistic radio station called WUSA. The novel caught the sour mood of the dwindling civil rights era and presaged the arrival of the counterculture. Stone was back in New York City when Kesey and his Merry Pranksters commenced the shambolic cross-country bus trip that Tom Wolfe chronicled in “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.”

But Kesey’s bus picked up Stone and his family in Manhattan and they drove around the city with the Stones on the roof, dodging tree limbs. It’s surprising Stone wasn’t knocked to the ground by one of those boughs. To read this biography is to watch him absorb the cuffings that life delivers at every turn.

When he hitchhiked, he was jailed for vagrancy. He was mugged in Cuba; his house was burgled. He flipped a car on the West Side Highway and stumbled into bar fights. The one time I met him, in 1997, this seemingly mild-mannered man was rubbing his chin because a “friend” had punched him in the jaw the night before.

He seemed Zen-calm in the eye of a perpetual storm. The drugs helped. Stone took anything and everything over the course of his life: peyote, quaaludes, smack, Ritalin, Halcion, benzodiazepines. He seemed to need these things just to get out of bed, the way a soldier knocks down a tot of rum before going over the top in battle. Bell nails the details: In the wake of the Manson murders, Stone was still smoking the pot he’d bought from Jay Sebring, who died on Cielo Drive.

Stone had his share of ailments. He had gout attacks that began when he was still in his 20s, for example. Sympathetic doctors gave him good palliatives. Bell suggests Stone wore sunglasses because his pupils were “shrunk to pinpoints.”

He drank oceanically. He liked to spend time with the actor Nick Nolte, who starred in a misbegotten film version of Stone’s 1974 novel “Dog Soldiers,” because Nolte’s idea of a good time in Mexico, Stone once said, “was to drink a bottle of tequila and lie down in the middle of the main street and see what happened.” It was the cigarettes, though — Stone had a three-pack-a-day habit — that ultimately did him in.

“Child of Light” is a sensitive and thorough biography. Bell knew Stone well toward the end of his life; the two traveled together in Haiti. The author explicates Stone’s fiction and expands its context. If this quite conventional biography never entirely takes off, it is rarely uninteresting.

Bell writes with special alertness about Stone’s marriage, which he calls “one of the most durable literary marriages of the American 20th century.” Stone and his wife, the former Janice Burr, married when he was 22 and she was 19. They were together for more than five decades.

It was by most accounts a strong marriage, but it was certainly an elastic one. The couple decided early on “not to be possessive of each other.” Robert had vastly more dalliances than Janice did — a woman in every port and two more at Yaddo, and he fathered a child out of wedlock.

There was voltage in his eyes: He was a storied raconteur; women wanted to be around him. About the affairs, Janice didn’t ask and Bob didn’t tell. But Bell underscores the loneliness and pain she often felt. The couple had two children. Stone is not, in this telling, an abusive father. But their daughter Deidre once told the Stones to watch Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining” because “it’s about our family.”

This is one of those rare biographies in which you don’t feel like skimming the first 35 pages. Stone was born to a single mother (he never knew his father) whose mental health was shaky and uncertain.

She was sometimes hospitalized, and Stone spent time in tough local boarding schools. Together they sometimes lived in crummy S.R.O.s; at other times they were homeless. Stone joined a street gang before he was expelled from high school and enlisted in the Navy. He later reported from Vietnam, a war he called “a mistake 10,000 miles long.”

In his best novels — “A Hall of Mirrors,” “Dog Soldiers,” “A Flag for Sunrise,” “Children of Light,” “Outerbridge Reach” — Stone drew from a deeper well than most of his contemporaries. He transmuted basic matter into something larger.

He had a foreboding feel for the things that slid beneath the surface of life. He could pin a milieu to the wall. In “Children of Light,” his Hollywood novel, he wrote: “There are people at this table who could vulgarize pure light.”

Stone was a strange pilgrim, a lonely sentinel. He said about his first novel what you could say about all his fiction: “I had taken America as my subject, and all my quarrels with America went into it.”

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates

EU News Digest Latest News & Updates